Negotiations at Appomattox, Part Two

Robert Menard

Certified Purchasing Professional,

Certified Professional Purchasing Consultant, Certified Green Purchasing Professional, Certified Professional Purchasing Manager

Editor’s Note: This is the second part of a three part series on the battle that ended the American Civil War and the negotiations between Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Union General Ulysses S. Grant. Part One is available at this link . It is hard to imagine in today’s instant telecommunication world that correspondence was done then by officers on horseback, allowed to proceed behind enemy lines to consult with counterparts. Such initial contact was followed by handwritten correspondence between the two generals, culminating in a face to face meeting and hand written surrender documents. Try to imagine the restraint exhibited by these soldiers whose job it was to kill the other side and destroy their civilization.

The cost in lives of the Civil War was about 620,000 men, an estimated 2% of the population at the time. Nearly as many men died in captivity during the Civil War as were killed in the whole of the Vietnam War. Hundreds of thousands died of disease. As a percentage of today’s population, the fatality toll would be about 6 million.

Lee and Grant were trained generals, educated in warfare, but most importantly, they bore the defining imprimatur of honorable men. As the war and its terrible costs dragged on, each was eager to end the war. It was becoming clear by 1864 that the Confederacy was on an irreversible slide. Grant noted in a letter to Lee that, “By the South laying down their arms, they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of lives, and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed.”

In order to appreciate the enormity of this quote, it is necessary to understand the interpersonal relationship of the two generals, both of whom were educated at the US Military Academy at West Point, NY. Lee was in is late fifties and Grant in his early forties and Grant had served under Lee who was chief of staff to General Winfield Scott during the Mexican War.

Negotiation Lesson Two Respect for the other side at all times

They had been opposing commanding generals for much of the Civil War. Both men were acutely aware of the enormous toll the war had taken in terms of blood, treasure, and sorrow. In March 1864, Grant made the unilateral decision to suspend the exchange of prisoners-of-war, harsh as it may have been on the prisoners of both sides. He reasoned, quite appropriately, that the exchange was prolonging the war by returning soldiers to the outnumbered and manpower-starved South.

In his memoirs, Grant wrote of the meeting with Lee and the subject of negotiations at Appomattox. “What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassable face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter [proposing negotiations], were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question, however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us.

Note the utmost level of respect Grant reserves for his opponent. He does not think of Lee as an enemy, an adversary to be sure, but also a man of feelings, commitments, and honor. Grant recognized the personality factors that play into negotiation and was scrupulously careful to try to understand Lee’s while controlling his own.

Negotiation Lesson Three Expect the unexpected

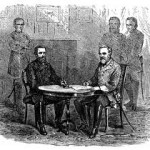

Grant would later write that “General Lee was dressed in a full uniform which was entirely new, and was wearing a sword of considerable value, very likely the sword which had been presented by the State of Virginia; at all events, it was an entirely different sword from the one that would ordinarily be worn in the field. In my rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, (and no sword) I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form. But this was not a matter that I thought of until afterwards.”

Grant would later write that “General Lee was dressed in a full uniform which was entirely new, and was wearing a sword of considerable value, very likely the sword which had been presented by the State of Virginia; at all events, it was an entirely different sword from the one that would ordinarily be worn in the field. In my rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, (and no sword) I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form. But this was not a matter that I thought of until afterwards.”

Grant had been ill the day before and was widely rumored to be a heavy drinker. A line, attributed to Lincoln in response to allegations of Grant’s drinking is, “If all my generals could fight like Grant, I’d send them all a barrel of Grant’s favorite whiskey.”

Could Grant’s disheveled appearance been due more to a hangover than other illness? Who knows, but without doubt, the appearance of the two generals created an obvious imbalance. Was power shifted by having the surrendering general out dress the winning general? Was this sartorial reversal an intended negotiation tactic by Grant? The answer lies buried in history.